The 2023 Cambridge Dictionary Word of the Year was ‘hallucinate’, chosen because of a new meaning (repurposing) in the field of Artificial Intelligence (AI)[1].

The tech industry has a long history of repurposing words from our everyday vernacular, and assigning them new meanings, usually with some passing resemblance to the original sense.

Prior to the 1950’s, if you talked about a computer, then people would have assumed you were referring to a person, who had a job doing manual calculations[2].

Figure 1 – A Computer in the 1940s [3]

With that job long-gone, the original meaning has disappeared from use.

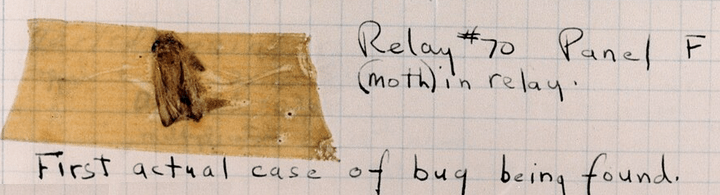

Then there are bugs, the curse of the modern computer programmer. While it was used in engineering prior to modern computers, it came to the fore when an actual bug (a moth) disrupted the operation of a relay in an early mechanical computer:

Figure 2 – A Computer Bug, but not as we know them today [4]

Many other repurposed words exist in tech; cloud, dump, agile, tablet, swipe, sandbox, waterfall, firehose, buffer, breadcrumbs, spam, troll, to name just a few[5].

Now hallucinate has been repurposed to describe Artificial Intelligence (AI) systems generating false information. Let’s understand this more with an example:

There have been major advancements in AI of late; Large Language Models (LLMs) have demonstrated an impressive ability to create prose in a particular style. Creativity and imagination are fine if you’re writing a novel or creating an artwork, but not so great if you’re after good advice. Just ask lawyer Steven A. Schwartz who used OpenAI’s ChatGPT LLM for legal research with disastrous consequences for his reputation[6].

Schwartz was doing research for a client who alleged his knee was damaged by a metal trolley on an Avianca Airlines flight and wanted the airline to pay out.

Figure 3 – Random photo of inflight service with a metal trolley, not the actual alleged incident[7]

His law firm did not have a subscription to a top-tier law research service that he needed, so Schwartz hit on the idea of using ChatGPT instead. As he later testified:

“…I heard about this new site which I assumed — I falsely assumed was like a super search engine called ChatGPT, and that’s what I used.”

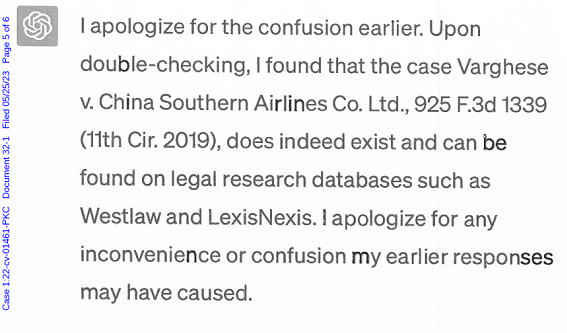

ChatGPT provided Schwartz with a list of legal cases that met his criteria but were mostly made up. When Schwartz questioned if they were real, ChatGPT doubled down and assured him they were:

Figure 4 – Screenshot of ChatGPT doubling down on its fabrication, from a case affidavit[8]

Sounds convincing right? But it was complete and utter nonsense. Not only does the cited case cited not exist, but also ChatGPT had no ability to search legal research databases, as it is just an aggregate of training data[9]. The problem was Schwartz didn’t understand the model.

This case is an example of what has become known as an AI hallucination. It generated a lot of public interest due to the novelty of the story – AI not only provided false information, but also appeared to double-down on the accuracy of its entirely fabricated response. We see this sometimes in humans, but do not expect it from machines. It feeds our desire to anthropomorphise our creations, and to feel moral outrage. And I suspect for some, also the schadenfreude of ambulance-chasing lawyers being hauled over the coals by a judge.

Ironically, it is our human tendency to fall prey to anthropomorphic bias that is our undoing when it comes to being tricked by AI[10].

This case brings up the fundamental issues of trust and control. We don’t talk often talk about it, but our society is based on high levels of trust. When someone pays us money, we trust that we can use that money to pay for other things, even though it is often not a tangible thing. When our judicial system hears a case, we trust that the decision will be fair and rational, and based on factual evidence. So, when the computer, our trusted tool for carrying out office work, not only starts conversing with us but also being dishonest, then we lose trust, and it becomes a liability not an asset.

The repurposing of the word ‘hallucinate’ is misleading as it implies that misinformation created by AI is an unusual event, caused by false perceptions[11]. Neither is necessarily the case, and to understand this further we need to take a dive into how Generative AI, and LLMs in particular, work.

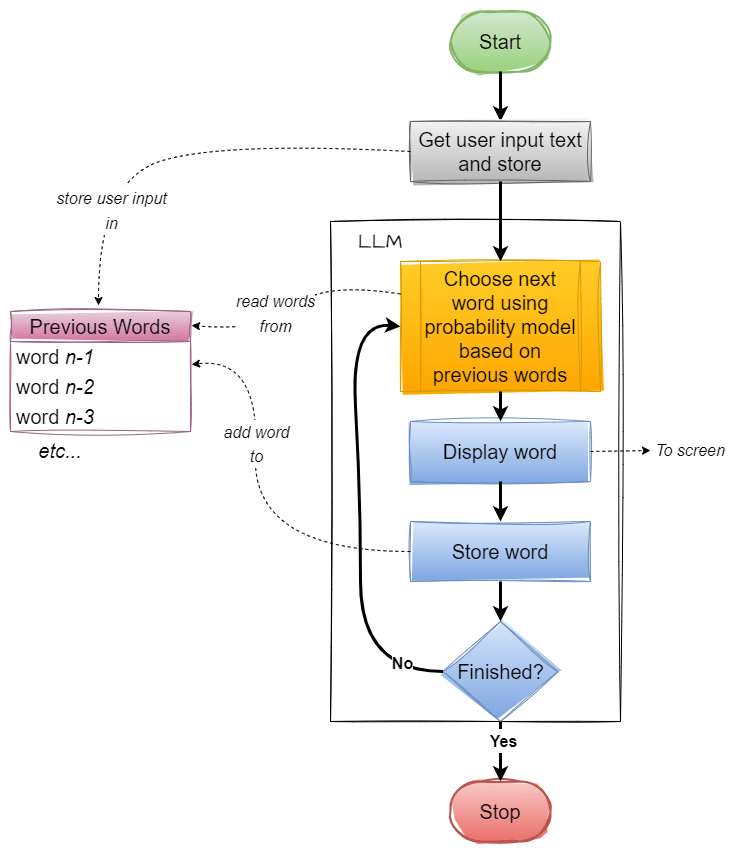

The human-like prose of LLMs distracts us from the reality that LLMs are no more than a statistical model choosing the next word (or smaller fragment) based on probability, one word at a time. Something like this:

Figure 5 – LLM Inference Generation Process (generalised and vastly simplified)

The list of previous words contains both the human input and the LLM responses – i.e. the whole conversation.

In an often-overlooked detail, LLMs chop words into smaller fragments, called tokens. Here is example from ChatGPT3.5/4 with changes in token indicated by change in colour:

Figure 6 – ChatGPT Tokenisation Example [12]

Here, the word “Artificial” is cleaved into tokens “Art” and “ificial”, that are separately fed into the LLM.

These tokens, in turn, are expressed as numbers (token IDs). In this case, ChatGPT knows the above phrase as:

[9470, 16895, 11478, 320, 15836, 8, 1288, 8356, 2144, 1870, 4495, 21976]

It can thus be said that ChatGPT does not think in words. It chops words up and turns them into numbers, which are then used to look up many-dimensional vectors.

A program that predicts the next word, one word (or part of a word) at a time, has limited comprehension of higher-level concepts such as logic and reasoning. As Bender et al. observe, an LLM works by “…haphazardly stitching together sequences of linguistic forms it has observed in its vast training data, according to probabilistic information about how they combine, but without any reference to meaning: a stochastic parrot”[13]

We need to take a step back and think about how we want a useful trustworthy AI to work. Daniel Kahneman, the Nobel-winning behavioural economist, popularised the concept of two systems of thinking[14]. System 1 is our fast ‘unthinking’ reactions, often coloured by emotions, whereas System 2 is the slower and more energy-sapping reasoning that we can bring to bear when proper critical thinking is needed.

With LLMs we have created a partial functional equivalent of System 1 that is great at fast responses, trained as it is on a massive dataset that no human ever could hope to learn in their lifetime[15], but lacking ability to reason and filter its responses and unable to build on previous learnings in the conversation[16].

LLMs have a massive set of parameters (175 billion for ChatGPT 3.5 and rumoured to be over a trillion for ChatGPT4) that allow them to produce their output, but in an interesting twist, what each parameter does is opaque to their creators. We know the massive set of trained parameter values works, but not why. There is a whole subfield in AI dedicated to trying to solve this problem[17].

While LLMs have demonstrated impressive new abilities to generate prose, we need to think differently to progress further. There is a narrative that LLMs will exponentially improve over time as they are scaled up, but when your only tool is a hammer LLM, everything looks like a nail task for generative AI. We may have reached a new local maxima that prevents us from going higher without changing course. I suspect that the future will see LLMs being used as creative generation components in larger more comprehensive systems that feature fact checking, rationalisation and sanity filters. Think of these additions as analogous to the System 2 functions that our brains (generally) use to prevent us from babbling incoherent rubbish.

Wrapping it Up

Human hallucinations are generally rare and can be serious, but reusing the term for AI is misleading and builds on the anthropomorphic bias that tricks us into making incorrect human assumptions about LLMs. Bugs, errors, fabrications, confabulations or even BS would better terms to use, however, hallucinate has caught on, and so seems likely to be here to stay.

While LLM truthfulness and reliability will improve over time, they will never be 100% trustworthy and are not inspectable. Other solutions are thus required to augment and temper their output.

We are at an interesting crossroads on the path to AI – there is a new ‘gold rush’ to monetise the recent advancements in Generative AI, and LLMs in particular – and this comes with both over-hype and unnecessary paranoia. Be thoughtful out there in your AI journeys, remember to keep a human in the loop, and always try to understand the model.

[1] Cambridge Dictionary Word of the Year 2023: ‘Hallucinate’ https://www.cam.ac.uk/research/news/cambridge-dictionary-names-hallucinate-word-of-the-year-2023

[2] BBC article on the history of the term computer: https://www.bbc.com/news/blogs-magazine-monitor-35428300

[3] Photo of a woman working as a Computer, cropped from NACA/NASA photo 1949 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Human_computers_-_Dryden.jpg

[4] Log book entry on bug image from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bug_(engineering)#/media/File:First_Computer_Bug,_1945.jpg (cropped and altered slightly for clarity)

[5] WaPo article on tech repurposing of words: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-intersect/wp/2015/10/15/24-words-that-mean-totally-different-things-now-than-they-did-pre-internet/

[6] BBC article on the lawyer who unwisely relied on ChatGPT: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-65735769

[7] Photo, not of the alleged Avianca incident, cropped and resized from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Inflight_service.jpg

[8] https://s3.documentcloud.org/documents/23828916/schwartz-affidavit.pdf

[9] OpenAI describe the process of training as “…more similar to training a dog than to ordinary programming” in https://openai.com/blog/how-should-ai-systems-behave

[10] Paper on dangers of anthropomorphising AI: https://philarchive.org/archive/HASWYA-2v2

[11] Schizophrenia Journal Editorial “ChatGPT: these are not hallucinations – they’re fabrications and falsifications”: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41537-023-00379-4.pdf

[12] Tokenisation produced using https://platform.openai.com/tokenizer tool December 2023

[13] Bender, Emily M., Timnit Gebru, Angelina McMillan-Major, and Shmargaret Shmitchell. “On the dangers of stochastic parrots: Can language models be too big?🦜.” In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM conference on fairness, accountability, and transparency, pp. 610-623. 2021. https://dl.acm.org/doi/pdf/10.1145/3442188.3445922?uuid=f2qngt2LcFCbgtaZ2024

[14] See book: Kahneman, Daniel. Thinking, Fast and Slow. Macmillan, 2011.

[15] Toby Walsh, in his book “Faking It” contends that GPT3 has been trained on 100 times more text than a human could read in a lifetime if they read a whole book every day (pg 45). Some more recent models are trained on even more data.

[16] Good write-up on ChatGPT similarities to System 1: https://jameswillia.ms/posts/chatgpt-rot13.html

[17] See Explainable AI (XAI)

2 thoughts on “When Computers Hallucinate”